Monday Medicine: Journey

05 April 2020

Michael Delaney takes us through the hero's journey of a film making its way to the hallowed screens of QFT. Read Part II here.

When one thinks of filmic journeys they might consider Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey”, a concept from his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Used now as a structure for screenplays, the “Hero’s Journey” – or “the monomyth” – is a series of story patterns which give shape to a cohesive, overarching structure without losing emotion or substance.

Think of it in terms of Star Wars. According to Campbell, our hero should live in an ordinary world where he is called to adventure, like Luke Skywalker intercepting Princess Leia’s message to Obi-Wan Kenobi. They should initially refuse the call, as Luke’s reluctance highlights, before meeting with their mentor and crossing over the first threshold into the new world, like Luke travelling to Aldernaan. Following this, our hero will meet allies and enemies (Han Solo/Darth Vader), approach their physical or mental “innermost cave” (the Death Star), face an ordeal (Obi-Wan Kenobi dies), seize a reward (Luke joins the Rebels), face more conflict (Luke choosing to fight the Empire), and face the final battle (destroying the Death Star) before, as Campbell states “returning home with the elixir” (Luke wins his medal).

It is a story we have all become familiar with. However, one journey you most likely aren’t familiar with is how a film, after it has made its way from the imagination of a screenwriter with a well-thumbed copy of The Hero with a Thousand Faces, through production and on to its distributors, makes its way to Queen’s Film Theatre.

The Ordinary World

In an ideal world there would exist a mythical database of upcoming releases which could be filtered by quality and audience interest to sort the wheat from the chaff. However, that would make Michael Staley’s job very boring. If you have seen a film at QFT in the past decade, it was almost certainly Michael Staley who chose it. That foreign language drama you loved? Staley. That off-beat indie comedy? Staley. That gardening documentary/35mm Jazz classic/Peppa Pig film? Staley/Staley/Staley. QFT’s Programmer has curated a programme of films and events for audiences for over ten years, injecting as much variety as possible from one month to the next.

Any future masterpiece begins its journey to QFT with a call to adventure – the preview screening.

Preview screenings can take several forms. “It's not possible to see every film in advance” Staley says, “so film festivals and exhibitor screening events, such as ICO Screening Days and access:CINEMA's Viewing Sessions, are an essential part of a programmer's toolkit.”

These previews give Staley and other programmers the opportunity to sample the best upcoming releases and discuss them with their peers. Despite the ability to watch films at home with the help of “screeners” – password-protected online versions of films – Staley tries to avoid them when he can. “Online screening links are vital” he says, “but if I can see a film in a cinema, where it's designed to be seen, then I should.”

But how to sift through the abundance of films to find the gems? Staley believes both experience and networking are important. “I've been programming QFT for many years now and have a pretty good idea which films will work for our audience. This is important when it comes to deciding what to watch at a film festival which might be screening hundreds of films over the course of a week. I can realistically only watch around 25 so I have to be pretty ruthless”. Staley adds: “[Networking] is often where ideas come from for collaborations and, of course, we get to talk to each about what we've seen - or should see."

Unfortunately, most of the previews Staley sees won’t be shown at QFT. For these films, unluckily, their call is refused. However, for those films that do make it through, a new world awaits.

The Innermost Cave

After choosing which films will grace QFT’s silver screen, Staley faces his equivalent of the Death Star – the monthly schedule. After discussing his plans with Head of QFT Joan Parsons, Staley will then approach distributors about screening their film. It is this side of programming that Staley describes as a “mystery” to most cinema-goers. The movie they are watching is only on screen as a result of back-and-forth negotiations.

As a small, two-screen cinema, QFT “slots” are sacrosanct. As anyone looking at QFT’s programming grid would see, there are a limited number of screening slots each month. Staley explains further.

“A distributor will usually ask for an 'all shows' booking for a new release if we're opening it on date. ’All shows' means giving it every available slot in that particular screen for 7 days (sometime 14 days). That's a lot of shows.”

What follows is a game of give and take. Sometimes a distributor will stick to their guns when it comes to slots. Others are more amenable to a deal. “At the end of the day, the distributor wants us to book their film and we want to show it”. Emails are written and telephone calls made and eventually a deal is agreed, after what Staley calls “some (usually) good natured sparring”.

It is a process that he says he enjoys, even if it is challenging.

“I LOVE working on the monthly programme. It's the reason I do my job” he says. “I want to offer a rich, challenging and entertaining programme which is why being good at negotiating with distributors is important.”

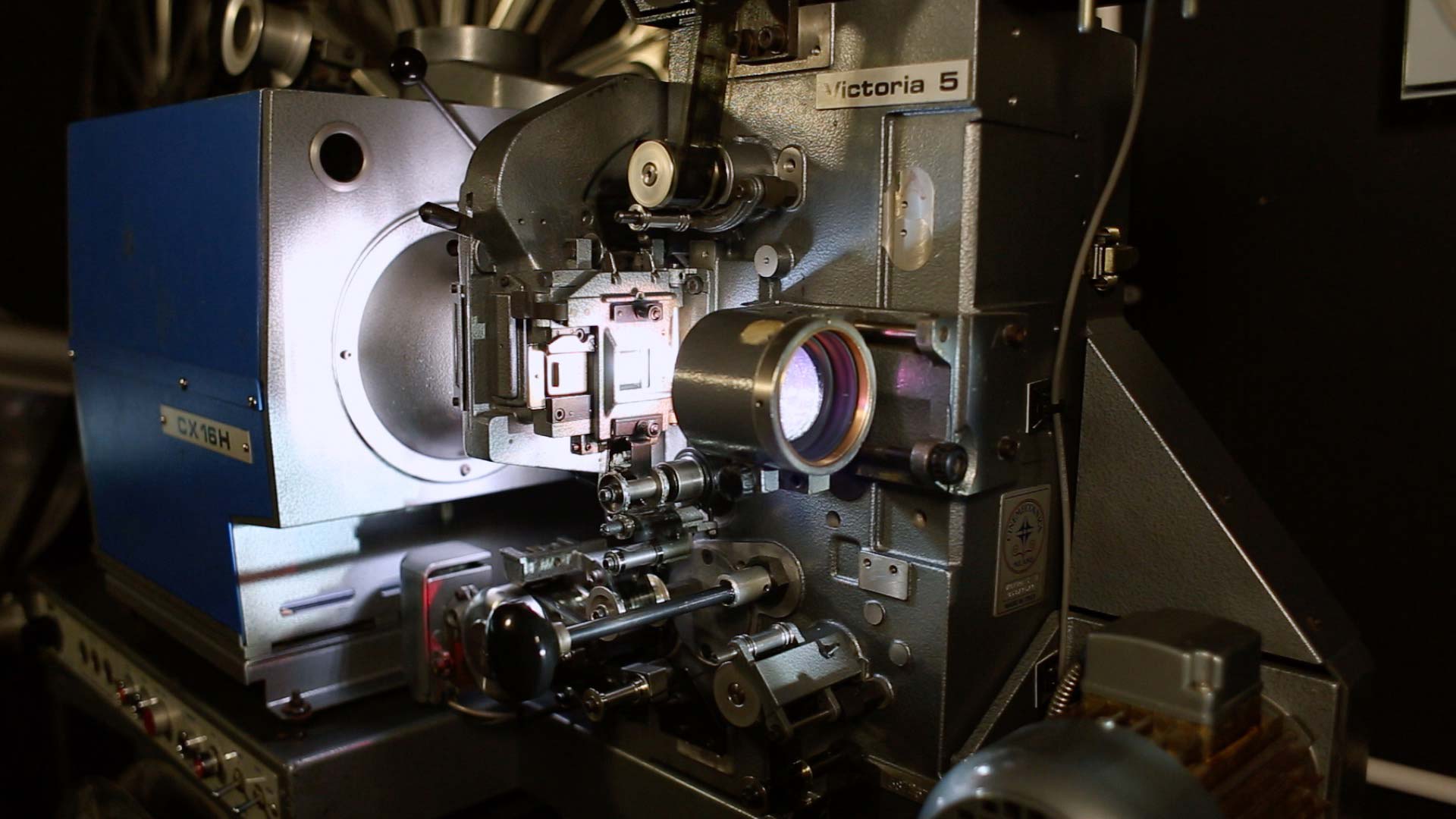

The next step, once the programme is locked in, is creating the printed programme. Staley starts sourcing images, writing copy, confirming production details and establishing details of special events, including sponsors and speakers. Decisions are made on how much space each film receives – what should get a half page and what a quarter page? What 35mm prints are screening? Finally a document is produced – in March it was over 7,000 words - which is then proof-read before arriving in the inbox of designer Ryan O’Reilly.

For Staley, creating the programme is a challenge he relishes. “I see it as a jigsaw puzzle. I love the process of choosing what will go on the cover and still get a thrill when I see the first proofs appear in my inbox.”

Staley liaises with O’Reilly on the look and design of the programme - with the cover image often debated thoroughly – and then, at last, a programme is agreed upon and sent to print. An intense period of work is complete and while Staley’s ordeal might be over for now, it doesn’t last long.

“We are always looking ahead. We work with several festivals and these are scheduled months in advance. National Theatre Live screenings are booked in months - sometimes years! - in advance too. And we keep a close eye on the release schedule to map out key releases in the year ahead. I feel proud when I send a programme to print - it's a marker in terms of feeling a sense of achievement in my job. And then I'm immediately on to the next one.”