Our City on Celluloid: Young Plato

15 March 2022

For the latest article in his Our City on Celluloid series, Fionntán Macdonald - LUMI young programmer - focuses on a newer entry to the canon of Belfast-set films - the recently released Young Plato.

Northern Irish documentaries have long been preoccupied with our troubled history, for good

reason. “Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it,” as the old adage goes, but

the unfortunate result of this is that our contemporary documentaries do not always feel, well…

contemporary. Young Plato (2022) breaks this mould by presenting an inherently modern and

deeply philosophical story, keeping one eye on the past while fixing its vision firmly on the future.

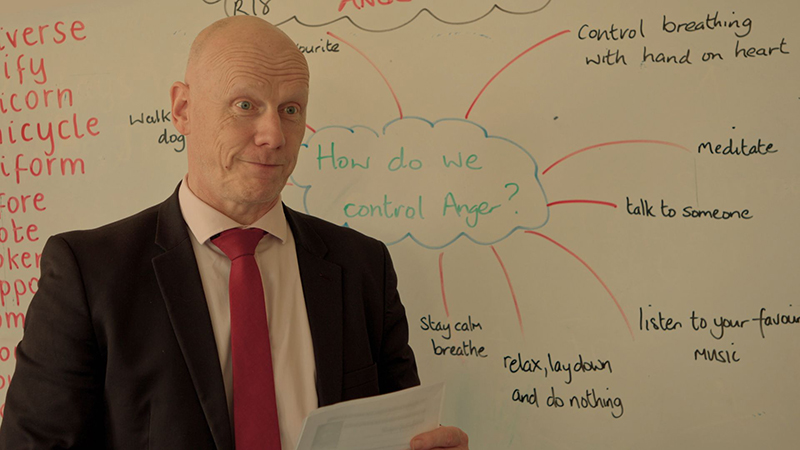

Following Kevin McArevey, the Head Master of Holy Cross Boys School, the film chronicles two

years in the life of educators and children who are navigating a landscape of sectarianism, substance

abuse and high suicide rates with the help of the great philosophers: Plato, Socrates and Elvis

Presley.

From the opening moments the filmmakers, Declan McGrath and Neasa Ní Chianáin, centre the

narrative with the introduction of Kevin, whose maverick ideas of introducing philosophy into

primary education are the film’s driving force. There’s a palpable charm to Kevin as a subject as the

filmmakers have savvily humanised him by highlighting his idiosyncrasies immediately (chiefly a

love of Elvis and his consistent habit of breaking into renditions of The King’s greatest hits). This

goes a long way to anchoring the film’s more serious themes to an empathetic figure.

“People have to be drawn in by a character,” noted McGrath at a recent Q&A screening of the film

at QFT, and the film’s cinema verité style will certainly draw you in. While fellow local stand

out I Am Belfast (2015) exists in what critic Bill Nichols identified as the performative mode, Young

Plato constructed in the observational mode which emphasises complete immersion over all else.

Filmed in fly-on-the-wall fashion without any talking head interviews, this film is far less formalist

and, as a result, more heartfelt. The hefty themes are addressed conversationally rather than directly

towards an abstract audience, which only aids in assimilating the audience into this community.

During the Q&A the filmmakers explicitly noted their absolute commitment to the observational

mode and this has informed the entire pace and structure of the documentary, as well as its

production.

Principal photography involved two years (on and off) of location filming in Holy Cross itself,

and the time taken to integrate the crew into the community pays dividends in the level of comfort

every character has with the observant camera. This was no accident, as Ní Chianáin had previously

worked on a school-based documentary: one which she says had to abandon a full year’s worth of

footage in the cutting room as the children involved would not interact naturally with the crew.

Learning volumes from this experience, the skeleton crew of Young Plato set up base in Holy Cross,

working there daily whether filming or not, until they became part of the furniture.

The result is some of the most naturalistic and unaffected interactions you will see on screen, lifted

from the almost 12,000 hours of footage captured on location. Due to the volume of footage the

film’s editor was brought in during principal photography to help shape the narrative and shear

away anything that didn’t advance the film’s message or expand on its themes, resulting in an

effortless flow of information on screen.

In this way Young Plato is constructed as a series of moments, personal and pastoral, tied together

by a central thesis. Appearing himself at the Q&A, Kevin spoke eloquently about his discovery of

philosophical thought at university and how his mission as an educator is to engrain the ethos of

“thinking about thinking” into his school. This emphasis on critical thinking and discourse is used

by the filmmakers as an allegory; an examination on this young generation's outlook and its contrast

to the past. History is touched on frequently, but never dwelt upon, and Kevin’s emphasis on

remorse when disciplining the children serves as an important parallel to reconciliation and prompts

some truly touching moments. Importantly, the film often cuts to Kevin’s own philosophy

lessons to further examine an issue, centring the narrative on a recurring motif while fluidly

introducing the input of the children themselves (fully fledged characters in their own rights).

Ultimately, Young Plato is, “a story of hope,” as McGrath introduced it: an empathetic exploration

of reconciling the conflicts of the past and the promise of the future. Doing a whole lot with very

little, this film may just forecast the future of Northern Irish documentaries.

- written by LUMI programmer Fionntán Macdonald