Exploring International Solidarity in The Black and the Green & The Ban

24 June 2024

LUMI Programmer Caitlin Sahin explores the shared themes of international solidarity in Docs Ireland films The Black and the Green and The Ban.

In 1969, a golden key to the city of New York was given by Mayor John Lindsay to Irish civil rights leader, Bernadette Devlin. The key was then presented in March 1970 to the Black Panther Party by visiting Irish republicans ‘as a gesture of solidarity with the black liberation and revolutionary socialist movements in America’. The intention of the trip to consolidate relations between Irish-Americans and Irish republicans in Northern Ireland reached a point of tension in this exchange, with Devlin’s explanation that: “My people”—the people who know about oppression, discrimination, prejudice, poverty and the frustration and despair that they produce were not Irish-Americans. They were black, Puerto Rican, Chicano.’ This is one example of the many links between the Irish republicans and BPP, with roots tracing to the 1960s civil rights movements, and further historically to the 1916 Easter Rising which reverberated to America through figures such as W.E.B. Du Bois. St. Clair Bourne’s 1983 documentary The Black and the Green illuminates this dialogue, by following five Black American activists and their Republican hosts, exploring commonalities and differences regarding their respective struggles, as well as highlighting the influence of Black resistance on the Republican movement.

For both the BPP and Irish republicans, culture was significant in constructing identities based in ideologies and mythologies respective to their own nationalist causes. Shared concerns between the American civil rights movement of the 60s and Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association were demands to tackle unequal voting, jobs and housing discrimination, as well as prejudiced policing. Institutional racism in the US along with the institutional discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland provided motivation for a later turn to militancy.

The significance of media manipulation of political representation was exemplified during the trial of Angela Davis, and later implicated in the representation of the IRA and Irish republicans to British audiences. Working as a philosophy professor at the University of California between 1969-1970, her media representation shifted from being a communist academic to a ‘black militant’. In 1970, Davis was charged with three capital felonies. She was held in jail for over a year then acquitted of all charges in 1972. Upon her arrest, the New York Times wrote, ‘the young black militant who has been hunted for nearly two months on murder and kidnapping charges, was arrested yesterday’. The verb ‘hunted’ evokes historic racist and animalistic representations of Davis as something uncontrollable while the reductive nature of the phrase ‘black militant’ reduced her identity to that of militant violence without further elaboration on her political ideologies. As representations of blackness were often distorted for mainstream media, Bourne’s dedication to documenting everyday life in black America preserved the resistant voices of the civil rights movement and transition to the Black power movement. He captured a significant chapter not only in black resistance, but spoke to larger historical movements of international solidarity.

In England, cultural theorist Stuart Hall offered an analysis on contemporary broadcasting of the republican cause, highlighting a similar case of political censorship akin to the trial of Davis. Hall stated in 1972 ‘what the general public knows about Ulster or Bangladesh it knows essentially from the media’. Describing the self-censorship of media under external political pressures, Hall writes:

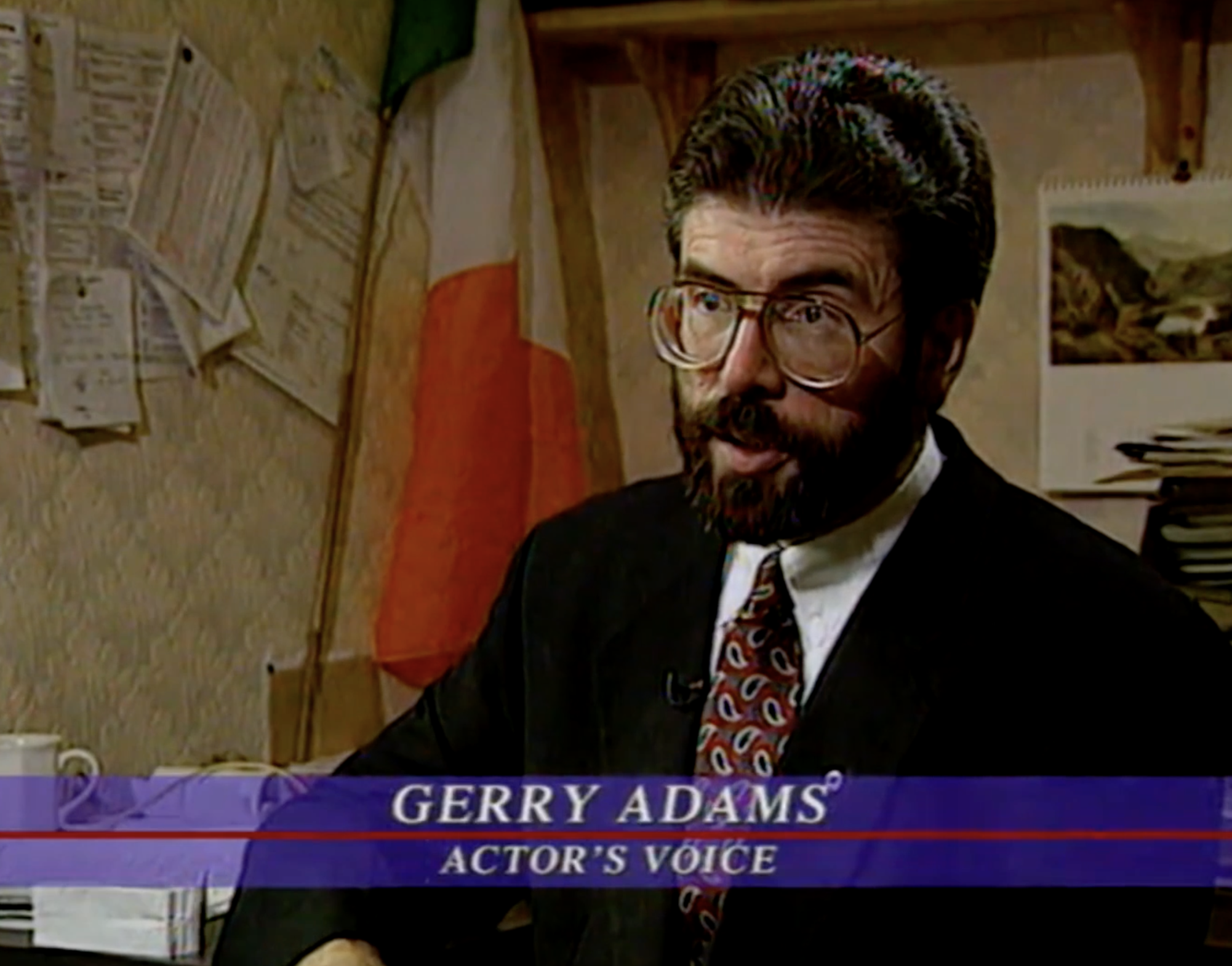

‘The broadcasters’ decision not to interview IRA spokesmen is the “free” reproduction, within the symbolic content of their programs, of the state’s definition of the IRA as an “illegal organization”; it is a mirror reflection and amplification of the decision, to which at present both political parties subscribe, that the IRA do not constitute a legitimate political agency in the Ulster situation—they are not within the definition of “parties” from which a bargain or settlement might emerge.’

The IRA were represented in British media without a subjective voice speaking for the organisation, therefore its representation could be used freely by the media to present them as an “illegal organization” without the elaboration of ideology to ‘constitute a legitimate political agency.’ This is not to say their actions were legal, however, in a similar manner to the idea of a ‘political prisoner’ and the trial of Angela Davis, the identity of republicans was presented only as that of violent terrorists, acting without political reason. Professor Meredith L. Roman described how Davis’s criminalisation worked to ‘reaffirm America’s self-righteous status as the leader of the Free World—a space where political prisoners did not exist.’ The 1981 republican Hunger Strike began as prior protests of the late 1970s failed in reinstating the status of political prisoners. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s public response to the hunger strikes was that ‘crime is crime is crime, it is not political’. Her reaction highlights the point of presenting revolutionary groups as solely criminals since the addition of ‘political’ introduces an ideological purpose incompatible with the law and the institutions which uphold it, therefore our ideas of equality, democracy and freedom are also thrown into question by the title of ‘political prisoner’.

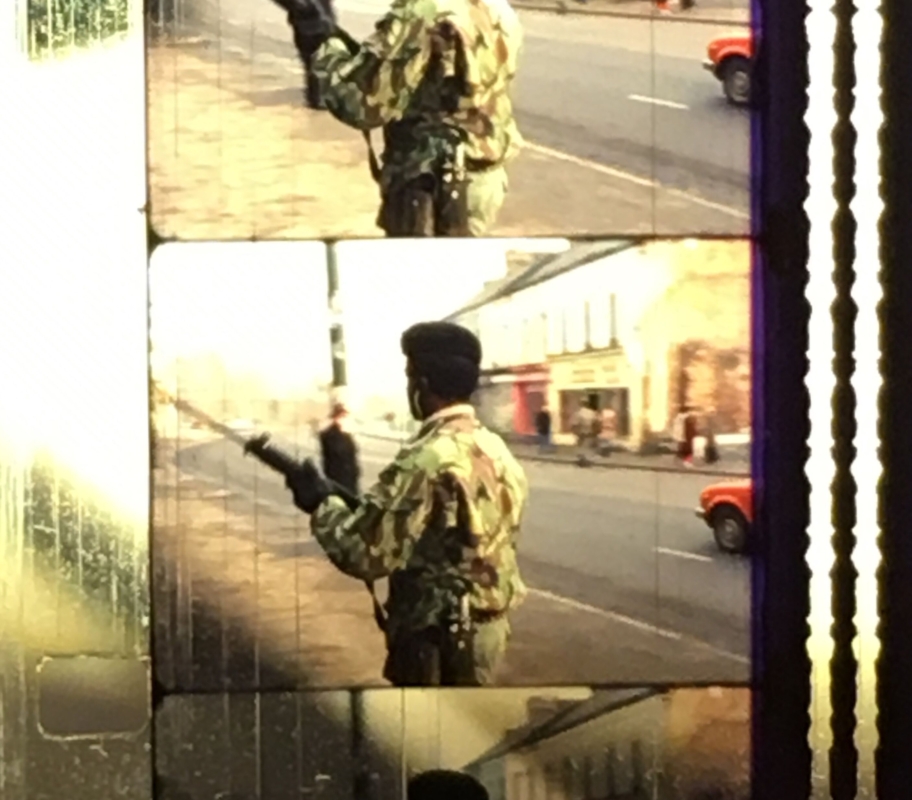

As explored in The Ban, a broadcasting ban prohibited the broadcast of direct statements by representatives or supporters of eleven Irish political and military organisations. The government ban was worked around through means of subtitles or dubbing, yet this would still remove a sense of tone, expression, and articulation. Thatcher intended to ‘deny the terrorists the oxygen of publicity.’ The censorship resulted in republican posters directly attacking the British media. One stated ‘If you don’t know what is happening in Northern Ireland, you must have been watching British television, listening to British radio and reading the British press’. Another used close-up photographs of an ear, eye, and mouth to indicate all forms of consuming British media were muting the issues of Northern Ireland.

Alternative forms of representation from murals, to posters, and documentaries offer articulation and public presence directly from the voices of those political activists involved, it is a space for international dialogue and parallels of struggle to emerge through conversations of solidarity.