Fantastic Planet: The Fantastic Life of Roland Topor

16 January 2025

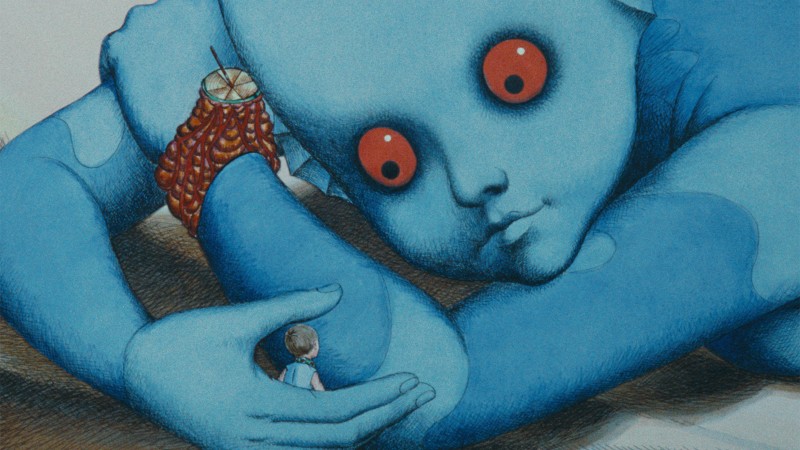

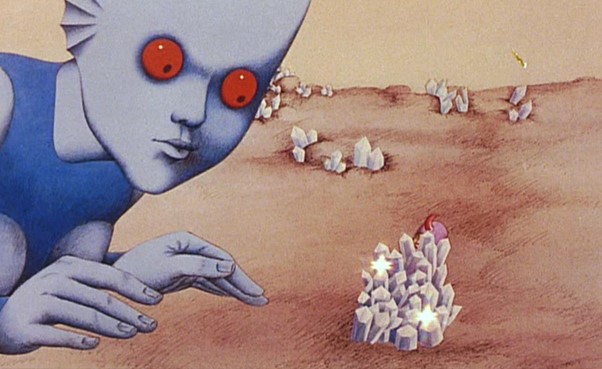

LUMI Programmer Dylan Kelly explores the life of Roland Topor ahead of our LUMI Presents screening of Fantastic Planet.

“le sang, la merde et le sexe” (“blood, shit, and sex”) – the manifesto of the surrealist illustrator, novelist and actor Roland Topor. You might not have heard of him – his stock has fallen in contemporary film-circles – but his eccentric output of the 1960's and 70's attracted the attention of many of European cinema’s countercultural icons. His most famous work, Fantastic Planet (winner of the Cannes Grand Prix Special Jury Prize in 1973) threatens to overshadow his diverse achievements, including the nightmarish novel The Tenant (later adapted into the Roman Polanski film) and his central role in the establishment of the short-lived “Panic Movement” with none other than Alejandro Jodorowsky. Like all great surrealists, Roland Topor’s life is as inexplicable as his art.

Cartoon by Roland Topor

That life began in jeopardy. Born of Polish-Jewish origin in 1930’s France, Topor’s family were forced into hiding from the Gestapo in 1941. Under pressure from their landlady to disclose the location of his father, Topor’s family fled to Savoy, where Topor was raised under a different name until the war was over. In a surrealist event that would inform his later novel The Tenant, the Topor family resumed renting from that same landlady after the war. Watching any interview with Topor, you may be surprised by his blasé attitude towards his past. Far from a self-serious artist, his interviews are full of tongue-in-cheek banalities about his “bourgeois life” and his refusal to acknowledge any great artistic motive behind his art. More conspicuous still is his childish shriek of a laugh, contrasting sharply with his quiet, almost mumbling voice – a characteristic that proved invaluable in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu (1979), where Topor plays the deranged Mr Renfield. Still, this coy denial of biographically informed art is a typical surrealist trick, and the narrative of dehumanisation and genocide in Fantastic Planet is an obvious response to that trauma. His friendship with Alejandro Jodorowsky (of The Holy Mountain and aborted-Dune fame) shows just how political the 1960s Parisian surrealists were willing to be. The “Panic Movement” that they founded declared that surrealism had become too mainstream. Their solution to this problem? To induce literal panic attacks in their audience through torturous theatrical performances, including the live slaughter of animals and sexually stimulating flogging. Thankfully, QFT will not be programming a re-enactment.

Topor stanning Nosferatu

Despite their undeniable transgression, most of these stunts feel dated. They lean into a particular avant-garde sentiment that has been the subject of contemporary parody and pastiche for decades now. Even today, most of the marketing for Topor’s illustration in Fantastic Planet targets the “Ultimate Trip” stoner audiences à la 2001: A Space Odyssey. But his illustrations for the films of René Laloux (including Fantastic Planet as well as the short films The Snails and Dead Times) continue to captivate audiences because they lean into this datedness. Topor’s cutout style is reminiscent of Terry Gilliam’s animations for Monty Python, and it risks falling into accidental comedy through this association, but he uses that style to depict such nightmarishly futuristic landscapes that are themselves reminiscent of Salvador Dali’s paintings. The films consciously exploit that whiplash between cliché and idiosyncrasy, creating a distinctly 70s vision of the future that has remains utterly singular to modern audiences.

Roland Topor’s life and work is criminally underseen and underdiscussed. As his back-catalogue of literary and theatrical works continues to be translated into English, it is the perfect time to familiarise yourself with his most famous work on the big screen. At only 72 minutes, you have no excuses!

QFT Screening of Fantastic Planet on Saturday 18th January @ 13:20