LUMI Reviews: The House Is Black

06 June 2025

LUMI Programmer Steven Burrows offers an analysis of the Iranian short film "The House is Black" ahead of its screening for LUMI’s Women in Iranian Cinema season.

“O overrunning river driven by the force of love, flow to us, flow to us…”

Upon her passing in 1967 at the age of 32, Forugh Farrokhzad’s tumultuous life and career had seen the poet and author garner much attention and importance in her native Iran, where her works had been banned for their feminist material. While her written work would understandably be the reason for her notoriety, she was also once able to share her gifts with cinema, with the experimental short, The House is Black.

Set in a leper colony in Azerbaijan, Farrokhzad’s sole filmic endeavour stands as an especially significant work of the Iranian New Wave. A prototypical film for the movement in many ways, but it sets itself apart by implementing Farrokhzad’s written style. She looks to reveal our own empathetic qualities and boundaries, challenging our instinctual reactions to sickness and isolation. To establish how the film achieves this more thoroughly, I will draw from two literary sources; Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor (1978) and Mary Ann Doane’s The Voice in the Cinema: The Articulation of Space (1980).

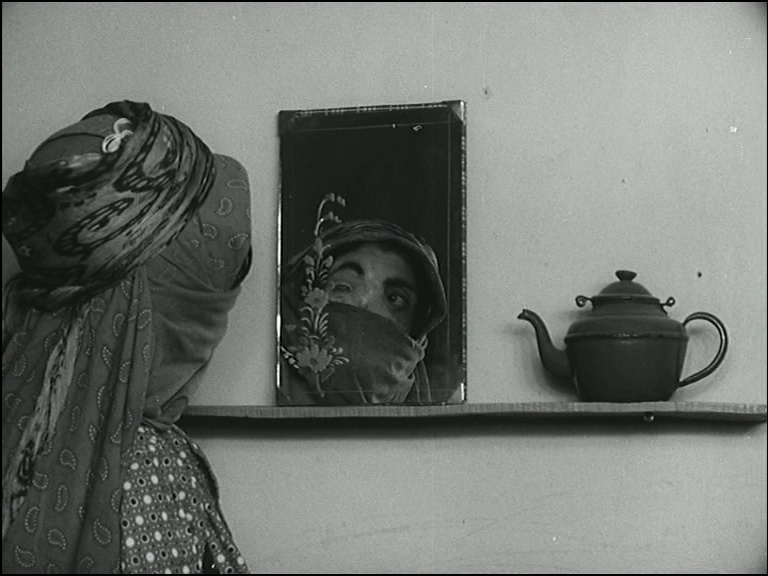

The House is Black is very delicate, occupying a space whereby it easily could have othered and objectified its subjects. Slow zooms, tight framing and widely haunting and upsetting ambience allow for some truly striking images of sickness and loneliness, but this imagery, while staunchly neorealist, also leans into the perverse and discomforting. We are even introduced with the line, “on this screen will appear an image of ugliness”. However, that discomfort and shock pulled from the spectator is integral to the purpose of Farrokhzad’s work here because we are intentionally being confronted, having our own immediate feelings and attitudes brought forward and criticised. She presents unnerving cinematic techniques and images to force us to consider why we may respond negatively. This enables us to work towards undoing our own prejudices but also simply captures those existing and cruel sentiments that have long followed lepers. Equally important to the film’s impact are Farrokhzad’s own capabilities as a poet and cultural figure, as she enmeshes her spoken word with that occasionally unsettling but always empathetic direction. Anchoring the short is a voice-off of such a proportion that it’s difficult to wrap one’s head around. The elegance and thoughtfulness of her own prose bleeds into passages from the Bible and the Quran, with such grand excerpts redefining the images displayed to us.

Doane’s writing on the concept of the “voice-off” unearths a transgressive interpretation of the voiceover that “constitutes a denial of the frame as a limit… [manifesting the body’s] inner lining”. The aim here, as the author puts it, is to “turn the body inside out”. Farrokhzad thus specifically utilises a religious voice beyond the frame and skin to render that interiority. She is exploring an intimacy for a people who had been solely defined by their illness. Doane’s writing is tied to the voice-off stemming from one clear figure, and uncovering their inner being, but we don’t find that here. Instead, since there is no physical, tangible figure to bind to Farrokhzad’s delivery, these layered passages become the spiritual, communal inner lining of this colony.

Incorporating her poetry and scripture readings with this direction in such a way that there exists a collective voice is the transgressive act; to find that voice and it be unhindered by image, physicality or sickness. Though Farrokhzad doesn’t simply give a voice to people and leave them without their own. Their grunts and shouts as they play football, singing, discussions with their teachers further reject the idea of constant suffering, misery and ugliness. In the latter example, a teacher asks one child why one should thank God for a mother and father, and the child replies, “I don’t know, I have neither”. The child is visibly upset but processes that without judgment or discomfort in the presence of his peers. In another instance, the teacher asks a boy to name some ugly things, to which he is told “Hand. Foot. Head.” as he smiles and a handful of boys laugh at their own expense. It’s disarming and authentic, and the neorealist approach Farrokhzad employs here and throughout neutralises the perception of people with leprosy as frightening or threatening. Of course, we must remember how those with leprosy were seen upon this film’s release (and still are), and it’s how Farrokhzad intertwines very intense imagery with her beautiful voice-off and this community’s voice that enables us to undo prejudices.

Doane continues to suggest the voice-off “displays what is inaccessible to the image”, and as discussed, uncovering that is what Farrokhzad seeks, but Doane also warns of othering subjects when leaning on it as an “isolated haven”. Where The House is Black sidesteps that, beyond the inclusion of the colony’s own voices, is in the authentic image. This leads me to Sontag. In her text, Illness as Metaphor, she contends with what she believes to be the very cruel and oppressive nature that comes with applying ‘significance’ to life-altering illnesses through metaphor, a way of victim-blaming that would establish a singular and inaccurate portrait of the sick. She is very succinct; “nothing is more punitive than to give disease a meaning — that meaning being invariably a moralistic one”. Few illnesses then, have had metaphor applied to them quite like leprosy, seen throughout cultures and history as a religious punishment, a moral affliction and a sign of great sin. The disfigured body was seen as the ultimate consequence for moral failing. Such social stigma is difficult to shake, the result being it, as Sontag relays, “[weakens] the patient’s ability to understand the range of plausible medical treatment but also, implicitly, [directs] the patient away from such treatment”. Regardless of how you find Sontag’s very strict assessment of metaphor here, it is true perceptions are quickly built up and established in the minds of many, especially when the attached metaphors are spiritual in nature.

Farrokhzad had to avoid perpetuating this, doing so by choosing to avoid metaphor in the sick image. Following a neorealist style, and in-turn laying groundwork for Iranian New Wave, she resists directly addressing mythology. Yes, she uses images which will incite negative feelings within the spectator, but that is to internally establish one’s own problematic sentiments, which are then taken down by the footage of normal life within the colony. Demythologising is the pursuit. I mentioned the disfigured body as a symbol of punishment for sin, another false image Farrokhzad confronts head on through visual style. She shoots close and intimately, in everyday circumstance; brushing hair, getting treated, breastfeeding, sitting in the grass and dirt. Palms and eyelids and nostrils exposed to us. Against still bodies of water, animals gripping their young, leaves fallen from trees. To normalise and demystify is, for Farrokhzad, to align with experiences and images older than can be comprehended, to treat illness as an act of nature to be nurtured and not feared or misunderstood.

Where Farrokhzad further succeeds and differs, and where Sontag has more room for debate, is that while I would agree having others apply metaphor to your illness will likely be oppressive, it doesn’t fully reflect the potential of independently applying metaphor to your own experience. Farrokhzad seems to recognise this, so refrains from interviewing the colony on how they perceive themselves, and only directly mentions leprosy in scientific terms. Even this is delivered by an unnamed man, removed from Farrokhzad’s spiritual voice. She presents the bodies, the actions, without othering, but allows the human condition to carry on through that inner being. Sickness and loneliness, and the want to be free from them, are feelings no one can avoid. Religion and faith in the voice-off then, aren’t simply to embolden the visceral, true image, but also to relieve. This response, much like what Farrokhzad chooses to show us, is natural. “An image of ugliness” is a misdirection. The ugliness is only as true as the spectator perceives it to be. Rather, it is a natural image, ultimately a beautiful and soothing one.